‘As an author of several influential and widely read books on art history and cinema, I’ve long been fascinated by the intersection of visual culture and its impact on our understanding of the world. This deep engagement with research and writing continues to be a vital part of my practice, fueling my creative endeavours with a rich tapestry of historical context, theoretical inquiry, and a passion for uncovering the hidden stories behind the art we love.’

I author books, reviews and articles. I have a regularly updated Clippings portfolio where you’ll find excerpts from some of my publications. I write regularly on the blog ArtHistoryFilm

I’m interested in asking questions like, what is art history and how does it relate to cinema? How is painting useful for filmmakers and how can I make it accessible for people more used to film? Is Painting a record of what the past looked like in the imagination of artists? What’s the relationship of film and painting in the use of visual language?

Does the traditional linear history of art still matter? Are we heading towards an “alternative” history of art? How can I consider non-Western art works and their influences on films?

I also explore how paintings can be representative of different genres, such as horror, sex, violence, realism and fantasy, and how the images in these paintings connect with cinema.

Articles

‘The Mystagogue: Philip James de Loutherbourg and the art of the occult’ Swedenborg Review 4 2023

Phillip-Jacques de Loutherbourg had a lot to recommend him. He was the youngest painter

ever elected to the French Academy and the first professional scenographer on the London

stage. Loutherbourg virtually invented special effects and devised the first-ever proto-cinema,

the Eidophusikon. He was a painter of stupendous skill and vision and taught Turner how to

paint light. So why has art history largely ignored Loutherbourg? If he appears at all, he is a

footnote.

Loutherbourg ‘the Mystagogue’ was an alchemist and a magician. Like Swedenborg,

Loutherbourg equally belonged to science and mysticism. Since his teens, he was a practising

alchemist and an engineer, devising mechanisms and pigments. And a magician exploring

arcane rituals and necromancy.

Reviews

Materiality Unleashed: Exploring the Sensory World of ‘Matter’

Matter Curated by Jo Dennis 23.10.23

This exhibition at Flowers Gallery Kingsland Road features various works united not by theme or artist identity, but by their lavishly tangible, haptic qualities. Curated exceptionally well by the participating artist Jo Dennis, the show focuses on materiality. Each work involves a unique – and often startling – selection, manipulation or transformation of materials that produce specific meaning or communication. Each artwork involves a unique and often surprising selection, manipulation, or transformation of materials, resulting in works that possess specific meanings and communicate in their own distinct ways.

Although not purely formalist, each piece in the show is articulate in its self-expression. The exhibition primarily focuses on the joy of texture and sheer materiality, allowing viewers to experience a bodily pleasure in the objects and their composition. read

Bliss in Berlin

Nazir Tanbouli: Postcards from Paradise 22.10.23

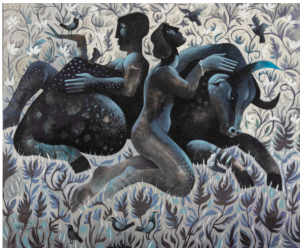

Cairo/London-based painter Tanbouli creates a bridge between the viewer and this otherworldly paradise. Each painting is like a postcard, inviting you to escape from reality and immerse yourself in the serenity and beauty of this alternate universe. The imagery portrayed in the exhibition invites contemplation and introspection as you witness the artist’s unique interpretation of paradise.

Tanbouli’s masterful use of colors and ethereal brushstrokes transports you to a world where time stands still and tranquility reigns. The exhibition serves as a reminder that paradise can be found not only in distant lands, but also within the depths of our own imagination.

The title Postcards from Paradise is evocative: the paintings represent a window into a tender, radiant world of timeless tranquillity, yet as ‘postcards,’ they imply that you, too, might be able to visit. These writings represent a celestial paradise, but it is not a theocratic heaven of judgement and reward. It is a place of tranquillity, devoid of strife, struggle, or fear. It is a garden where humans and animals come together to delight together. Tanbouli demonstrates the folly of human supremacy and exposes it as a fabrication, rejecting the concept of the ‘savage’ and the hierarchy of species.

Tanboouli’s work has traditionally included therianthropic – human-animal hybrid – characters such as the centaur and the minotaur, as well as creatures of his own devising. These forms reject the ancient Greek concept of human superiority in favour of the Egyptian method of combining the human and the animal to create gods. The god’s animal (or material) nature is regarded as equal to his human (or intellectual) nature. read

Books

‘Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr and the World of Dreams’, The Palgrave Handbook of the Vampire ed. Simon Bacon 2024

‘Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1932 film Vampyr was an abject failure upon release. Parts of the film have been lost, and Dreyer heavily reedited it due to censorship. Thanks to recent restorations, we now have a high-quality version that is at least a facsimile of Dreyer’s work. But assessing the film is not easy because it is so unusual; the moment one grasps the story or its characters, they seem to slip away in the dreamlike mist that suffuses every frame. Strongly influenced by visual art, Vampyr is a work of startling beauty and maddening mystery; it is a vampire film like no other to date.’

‘The Driller Killer: Artistic Precarity in the Downtown Scene’ in ReFocus: The Films of Abel Ferrara ed. Florian Zappe University of Edinburgh Press, 2025

‘The Driller Killer is written and directed by Abel Ferrara and stars himself as Reno Miller, a struggling artist who starts to hear voices and has disturbing hallucinations, which leads him to become a serial killer, using a power drill as his weapon of choice. After murdering several homeless alcoholics in his Lower East Side neighbourhood, he decides to take revenge on the people he believes are responsible for his current situation. However, as the violence escalates, Reno’s mental state deteriorates, and he begins to lose his grip on reality. It becomes clear as the film progresses that the use of murder as a metaphor transforms this story of psychological self-torture into what would come to be called a ‘slasher’ film, providing the audience with the gory delights of the genre while also compelling them to ponder the struggle of the artist.’

Art and the Historical Film: between Realism and the Sublime. Bloomsbury Press 2022.

‘I am at a symposium of the world’s leading art historians, in one of the world’s great museums. They are talking about Michelangelo Merisi, or Caravaggio (1571–1610), the first and perhaps greatest painter to show how high drama can be made by painting light and shade. His mainly religious pictures bring the often violent and dramatically spiritual world of the Old and New Testaments to life. The experts speak of everything to do with Caravaggio: his teachers and clients, his acolytes, his lasting influence, his tumultuous personal life. The word that keeps coming up repeatedly is “cinematic.” Caravaggio is “cinematic.” Yet the term is never examined or defined. We all just “know” what it means. One famed art historian posits, not without a note of disdain, that Caravaggio is so popular in today’s museums because he is so “cinematic.” The next speaker points out that his legacy is so deep-rooted because it is so—you guessed it—cinematic. Another one remarks that the painter’s greatest works operate between the cinematic and the realistic. Someone notes Martin Scorsese’s well-known love of Caravaggio. Why are movies constantly intruding on a discussion of early modern painting?

The term “cinematic” appears frequently and anecdotally in discussions of paintings but is rarely explained or defined. “Cinematic” means “of the cinema”—yet it is used to describe paintings from the baroque Italian Caravaggio to the modern Canadian Alex Colville (1920–2013) (Cronin, 2017, 62). The “cinematic” painting is a persuasive image that communicates various things that make a still image resemble or recall a filmic image. This use of the term “cinematic” could only come into being once cinema (the moving image) became a common language applicable across other art forms. The cinematic image communicates movement and a sense of time; it communicates space through perspective and depth of field; and it communicates sound through the visual rendering of imagery such as steam, machinery, the active presence of noisemaking elements (e.g., mouths open and shouting), or deliberate silence. Activities appear to continue outside the picture through subjects moving out or into the frame. Areas to consider in terms of the “cinematic” painting are its composition, color, and tonality, lighting, mise en scène, gesture, and the illusion of movement. Above all, the cinematic painting offers the possibility of a story. If we consider the gigantic Burial at Ornans (1849–50) by Gustave Courbet, we start to wonder, who are these people, and who has died? What does it feel like to be one of them, mourning under that louring sky?

Likewise, it is not uncommon to find the word “painterly”—again, undefined—used to discuss the visual style of some films or directors. Still, tableaux have appeared since early cinema, but “painterly” does not mean that the film is “like” a painting. Rather, the film style recalls a painting or paintings. As we will see in the case studies, the painterly film can successfully employ the same visual elements to convey the desired mood in a painting: composition, color and tonality, lighting, mise en scène, the illusion of motion or stillness, and gesture. Filmmakers as diverse as Uli Edel, Kelly Reichardt and Peter Greenaway, Jean-Luc Godard and Julian Schnabel have been called “painterly” for their style (Berger, 2014, 259). But painterly imagery can do more than that: it can rhetorically convey a sense of “high culture” by linking the filmic image to the high-art image, as an attractant to persuade the viewer they are watching a “quality” film (245McIver, 2018, 310–17).’

Art History for Filmmakers Bloomsbury Press 2016

‘Films are stories; filmmaking is storytelling. Storytelling is one of the oldest human activities. In the era of human history before written language, human storytelling was represented visually. From the cave paintings of Europe to the rock carvings of South America, visual narratives that tell stories proliferated. Filmmaking is simply one of the most recent manifestations of the human desire to tell stories. Filmmaking seems to have solved the ancient problem of bringing together visual representation, traditionally done through art forms such as painting, and time-based representation, traditionally done through art forms such as reciting or reading the written word. Cinema allows stories to be told visually over time. Although this may be seen as an innovation, it actually is something that we humans appear to have wanted to do for a long time.

“On stone, on wood, on canvas, on film,

electronically . . . the idea is what never

changes.”

—Vittorio Storaro, cinematographer

Philosopher and theorist Roland Barthes said that the world’s stories are innumerable, and that “the story exists at all times, in all places, in all societies. Storytelling starts with human history itself.”1 Barthes concluded that storytelling is “just there.” It is a part of life. Different types of research, such as anthropological research by Claude Levi-Strauss and psychological research by Carl Jung, showed that there are not only many different stories, but within those stories there are patterns or structures that recur beyond the individual control of the storyteller.

More recently, the art historian Ernst Gombrich proposed that one of the things that has made Greek art so enduring and successful is the way it is rooted in Greek storytelling. It is true that the popularity of stories such as the Iliad and the Odyssey had a profound impact on the development of the visual arts. Greeks put stories on their household objects, such as vases and dishes. Greek theater boasted elaborate masks and painted scenic design. But we can go back even earlier: if we look at the Egyptian pottery used by ordinary households, far away from the official art of the Pharaohs, we can see that painted images from myths and proverbs were part of everyday life.

If stories have been with us since our earliest times, as Barthes claims, then so has visual art; and more often than not, they have gone together. Storytelling is so pervasive that it appears to be hardwired into our whole way of understanding ourselves and one another. For millennia, important cultural stories were kept in the heads of storytellers, as knowledge was passed down from generation to generation. We call this oral culture. However, we can see that before written language, early human societies developed the means of visual storytelling. Whether it is the remarkable cave paintings in Lascaux or the petroglyphs in southern Egypt, we see images painted on walls or carved into rocks, and these images are organized in such a way that they tell stories. The first formally constructed narratives that we can read, because they relate to or accompany a written text, come from Mesopotamia and Egypt. The Book of the Dead explains what the belief systems were for the ancient Egyptians, and many other texts provide further examples of Egyptian mythology. But it’s when we actually look at the papyrus drawings, the temple friezes, and the tomb murals of ancient Egypt that these stories of death and rebirth really come to life.’